[Notes from my Little Letter Republic]

Whenever I feel plucked out of time, or stumble into a trough of aimlessness, or when philosophical questions addle the mind, I shake myself out of such lethargy by taking to one of the oceans of intellectual inquiry which in themselves are enjoyable and lend little prospect for my own career advancement: languages and mathematics.

This January was no different. Like the Finnish tradition of forswearing alcohol for the month of January, I put down the bottle and picked up a different intoxicant: Biblical Hebrew. Endeavoring to learn Genesis 1 and some few prayers, I managed to become significantly more comfortable with the “alephbet” and to build a bit of vocabulary before the old desire for practical advancement and struggle came back to alleviate my self-imposed relaxation. Similarly, I made several advancements in my deployment of integral calculus and spherical trigonometry.

And thus, after plucking the first fruits from the tree of knowledge, I stole away from the garden and went back to researching and writing essays. One on Milton-based humanities curriculum (John Milton) and another on reforming the aesthetics of the St. Louis Science Center.

This year was the biggest work change in 5 years, as I was finally able to reduce my workload from 3 full time jobs to 1.5. Over the past 6 months I have offloaded 96% of my administrative duties on one campus and dropped teaching two courses. So now I am only executive director of one campus and a teacher for three courses.

I spend a lot time staring at financial models, which I enjoy, talking to students and colleagues, which I enjoy, and running the gauntlet of open houses, follow ups, enrollments, check-ins, re-enrollments, update emails, hiring, follow ups, and subbing.

Now teaching at a a classical, catholic, hybrid school is one of the best places one can be. It is intellectually stimulating, the colleagues are intelligent and dedicated, the students are interested and engaged, the vibe is low-tech and bookish. I am raising my kids in a community of other parents who are also raising larger families, and so we have a deep solidarity.

Because of my reduced workload on the two home days I spend 5 hours working and 5 hours with the kids while being the executive function for my son in his home day work for kindergarten. That home day work takes about 45 minutes — usually spread out over an 1.5 hrs.

I am slowly figuring out how to work the finances of the school better so that we can compensate our full day people: if we found the donor who could make that happen, we’d easily be the best educational institution to work at in St. Louis. We’re already extremely close. My philosophy is “hiring is policy” and “quality of life is half compensation.” Or as I sometimes say; it’s a phenomenal place to work if you can afford it!

Last semester I taught two Latin courses, Geometry, Chemistry. This semester I have math, Latin, and moral philosophy.

Latin this year has been more fruitful than normal. Teaching the Aeneid in Latin is always a treat. And Vergil’s poetic style, my Lord, there is nothing like it! “Sink their submerged decks!” or “Disiectam Aeneae, toto videt aequore classem,” which can’t really be translated justly.

And this year I read more of the Roman historian Sallust in Latin, whose opening to Bellum Catilinae stirs up moral and intellectual ambition in the soul. But Leibniz’s Latin mathematical writings were especially fun and clear. It felt especially clarifying to be explained quadratures in Latin.

And just as sweet, since I have a colleague who delights in Latin, we together read Latin poetry together this year.

One of my favorite things about my local friends is that we read and discuss poetry together. I highly recommend finding friends who will do this with you!

I think often about what place I want to build for Latin in educational culture. I rely on the analogy of music. Latin is an instrument unlike other instruments. Why learn to play an instrument, but for the pleasure of being the conduit of the music? There is no way to get the pleasures of Latin without reading Latin, just as there is no way to get the pleasure of musical performance without playing the instrument. And because Latin grants access to particular cultures, if you want the ideas from those cultures to be part of the makeup of your soul, then you will want Latin – for law, for poetry, for hymns, for medieval philosophy and theology, and the early stages of the scientific revolution.

It’s embarrassing to me that my favorite ancient texts are actually almost all in Greek. Plato, Thucydides, Ptolemy, Archimedes, Aristotle… Greek has the best material, superior to Latin. And my Greek is out of practice. Yet by being the language of administration, Latin became the language of Western Europe. There might be a lesson there about the relationship between academic and civic language and culture. Perhaps if general Belisarius had succeeded in conquering Italy…

Antigone Journal has an ongoing contest for contemporary Greek and Latin editions, the prize being a complete Loeb Classical Library. I am excited about this, because there is some prospect for building more intentional living communities of classical learning, despite the falling numbers of departments and programs. The National Latin Exam, for example, continues to decline in number of participants, but the bleeding, I predict, will stop in the next 5 years if not sooner.

And even more exciting is that we will unlock the library of Philodemus using all that AI compute. It really has never been a better time to brush up on your Ancient Greek!

In Moral Philosophy, I finally have each of my lectures thoroughly worked out enough that I can compile my handbook for Applied Virtue Ethics with its tour of Kant, Mill, Aristotle, and Aquinas. What I really want to get across is a theory of justice which takes seriously justice in exchange as the form of justice which undergirds economics and much of daily life, and prudence as a personal art of expected value calculation. With a proper theory of double effect, I can help vastly improve reasoning in several areas, from clinical trials to immigration to national defense and romance. I especially want to challenge Catholic relativism in matters of prudence, which is a widespread issue, and provide a theory of justice that can clearly ground higher quality Catholic social thought.

My reduction in duties has gone well. At my peak pain point I was running a school, dean of high school at a different campus and teaching 8 courses across two campuses. So I know I have a great capacity to run on all cylinders.

And I will take on new projects in the future, but for now I am trying to explore, explore, explore, and resisting the sultry and racy seduction of new commitments, whose lips drip with the honey of deception and whose eyes shine with the meretricious allure of the oxygenless void.

The big events of this year for me have been recruiting one of my friends back into St. Louis to teach with me, hiring a former student of mine and team teaching with him, joining the Center for Educational Progress, visiting Ghana for the Emergent Ventures African and Caribbean conference, and presenting at the Fitzwilliam Seminar on Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago.

I am really proud of my friend Jack for finally launching the Center for Education Progress, which he has been talking about in various forms since at least 2018. So far the organization has an impressive list of allies and has published many excellent essays over at educationprogress.org. I have been able to assist the marvelous team on the policy proposal document providing guidance to certain government agencies, and I hope to keep working on some more projects soon.

I have also enjoyed befriending Anjan Katta and learning from him about the very cool hardware stack currently deployed in the Daylight Computer and possible futures there. I think the tech he has in the pipeline is really phenomenal. I look forward to seeing those iterations and being some contributor to his work’s success.

At EV Arlington, I made several new friends. Fergus let me stay in his room when my flight was cancelled, and Dan and I solved the mystery of the CCP scriptures. I suppose the message I took away from that conference was “Keep building your own society.”

My first time in Africa was for this years Emergent Ventures conference in Accra. These are observations from my green eyes.

It was more difficult to get into Ghana than expected. Getting the yellow fever vaccine required 16.5 phone calls and hunting for regulatory arbitrage. The unsecure visa portal stole my credit card, and when I messed up some paperwork the consulate was unresponsive. Once en route, though, it was easy entry into the country, and I found friends in the DC airport, Sebastian of Panama and Lamin.

My first impression of Accra was a deep inner peace at the high quality queuing at the baggage claim. The British did their work well, I thought to myself. Ghana was extremely safe. Jerry Rawlings, sir, you did in fact set the society on a peaceful path. One could tell by the posture and body language of people that the expectations for social interaction were positive (and I don’t mean interaction with me – a comparatively rich tourist). The general tenor of the streets was of safety.

My second impression of Accra was that the roads are good. We drove down the airport drive and the road was perfect. The minister of defense and some other ministers tragically died a few days prior in a tragic helicopter accident. Our bus driver blamed the cheap government for buying unreliable Chinese helicopters and not servicing them properly. And now as our conversation about culture turned to the finer points of the origins of Accra neighborhoods, the road literally disappeared at a major intersection. What is this? Why is a major intersection missing street? It would take a single day to fix this giant welfare loss. 50 mph driving suddenly slowed to 5 mph and into a great cacophony of chittering beeps as cars, trucks, vans and transports signal, hoot, hand gesture a negotiation through the intersection. It was a kind of beautiful harmony that I grew to love. The beauty of emergent order and communication on total display! But the achievement of infrastructure is to, you know, decrease the chaos, and increase the speed.

This led me to a second observation about the cars themselves. Old, beat up, painted and repainted coups were super common. Seeing people zip along in their cars, I could feel the love of cars throughout city. People love their cars and want to keep them going as long as possible. At the same time I was impressed by the number of new Kias, Hyundais, I even saw a couple Honda Accords. The frugal lower-class altruist and stingy saver within was almost offended: “You took out debt to buy that!” But I thought of the Queen song “I am in Love with my Car,” which basically justifies car culture on its own. Pace, walkability enthusiasts.

The third impression I had of Accra concerned labor. I have never seen intersections lined with people selling snacks and doodads in such numbers – one person was even selling a nail clipper set – nor have I seen such a high number of people doing very similar jobs, taxis everywhere, 5 porters at the hotel door, three clerks at the desk, several pool boys – a very visceral oversupply of labor. Immediately my mind started turning on how to turn the labor force into higher value occupations in as few steps as possible.

My goals in Ghana were to learn to negotiate prices, learn why every African independence leader was a socialist, and discover how to get around in an African context.

A group of us went to the Tetteh Quarshie art market via two Ubers. Unlike in the US where Uber drivers seem to lease richer vehicles than they should, Ghanians seem to be more realistic about what vehicle they will drive in. It took about 30 minutes to get from Labadi to the art market, but the drive was a good look at the city. I saw a perhaps vacant Willis Towers Watson building sporting the 2017 post-merger logo. So maybe it was still in use? The last Google review was from 6 years ago. And there is the possibility the building has nothing to do with the American company.

The roofs of almost all the building in the city were corrugated iron, a material I know little about, but is apparently the go to for shelters of all sizes and costs. The church roof was iron, the shack, the barber, the fancy restaurant, all corrugated iron. Some houses had large rocks sitting on the roofs providing additional weight to the slices of metal perched conspicuously over a leak.

They say the city proper of Accra has 2.8 million people and the region has 5.4 million. But the traffic was none too bad, except at night. Then it was very slow going. The opposite of, say, the 270 belt in St. Louis which is jammed before and after work (Lord, make haste to send congestion pricing!). Why are there major traffic jams at night? It only took me a minute to unravel the mystery. During the day maneuvering around pot holes is easy – at night very difficult. So night traffic is perpetually in molasses. Now while my urbanist friends will talk about the need for bike lanes, public transit, and improved walkability, the real issue is road quality. Throughput. There is plenty of transit available. Vehicle ownership is clearly not necessary to get around in Accra, but if you want to fix congestion and reduce pollution, repair the roads.

When we got to Tetteh Quarshie I was determined to hurl myself into the arts of the market. It was a single covered basilica with shops on either side. Some people were makers but most were resellers. The shops were frequently the size of a dining room, lined with shelves, art, knickknacks, doodads, and a man or woman strongly encouraging you to come in for a look. “Sir, Look! What do you like? Sir, come in!” Some were more insistent than others.

I had some people show me some art so that I could get a sense of what the motifs were, what was common and what was uncommon. I found an old seamstress putting together dresses, and knowing that my daughter was likely bigger than a daughter of the same age in Accra, tried to find a dress that seemed the right size. She insisted that the one I was interested in would fit her, but I wasn’t so sure it would be big enough to grow into, but merely fit for the month. We went back and forth on price as her radio played an English language political commentary on the spiritual dimension of Ghana’s woes. She was mildly disappointed, but we settled. She tempted me to buy something for my wife. But I told her such a venture was too risky.

Sam E. and I found a friendly gregarious shopkeeper and asked her how to negotiate prices. She was a special type, because the normal procedure is you ask how much, and they make a starting bid. It is rude for the buyer to make the starting bid. Nonetheless, this giddy gal was happy for Sam to make the starting bid. And he shook and trembled and exclaimed he had no idea what makes sense to offer. She reassured him, Say what you think, and if I don’t like it I’ll say no. This led into a discussion about the game theory of prices. He’s afraid of overpaying, and he doesn’t know what prices make sense. Then we started talking in hypotheticals, if I were to offer 50 Ceti for this, what would you say? Hypotheticals made it easier for us Western boys to get in the swing of things. Sam made an offer and she immediately accepted, and he told her that that indicates he should have offered lower. She denied it! But he reasserted the veracity of auction theory.

When I returned to the market after a break, my crowd was gone. I went and talked with the shopkeeper at the entrance, and tried to buy some knickknacks for home. I won some respect for having eaten goat fu fu, which indeed was good. We went back and forth on price and meanwhile I pleaded ignorance about the relative values of things. So I got her to discuss expected prices of art (which she didn’t carry), taxis, and so on. Part of that was so that I could budget my limited funds, and part of it was so that she could figure out what price she could offer me for her wooden turtles, and I could start calculating the value of labor. Nonetheless, she was older and more experienced and pulled a couple of slight exaggerations on me in the course of our friendly discussion. For example, she knows what she pays for a taxi, but didn’t want to be fully honest about what price I am going to get offered, which was about 2x that.

She has the best location in the mall, so I asked if she has to pay extra to get such a good spot. She said no, everyone pays the same for their lease. I was visibly shocked. But you have the best spot! I purchased my turtle, and she gave me instructions on where to go to find a taxi. She also said if I wanted the real experience, I would ride in one of the 12 passenger buses that shlep people around and always have a 17 year old boy hanging out the window hooting and hollering. I wanted to do that eventually, but never had the chance to spend 3 hours getting lost in Accra, which is what I would budget for such experiences.

Instead I found a taxi, and that guy dug in on a price that was almost 2x the standard street price. I negotiated him down 15% since I thought it was a 30 minute drive to Labadi, because that’s how long our Uber took. Apparently our Uber was as incompetent, as the taxi said they are, because it was only ten minutes back to Labadi.

Why do all African independence leaders believe in collectivized industry and state run enterprises and import and export tariffs and all these other terrible economic policies? The answer I was given over and over again at the conference was that Anglo economics and Anglo politics were not considered separable. If you are rebelling against colonialism, by necessity you are rebelling against capitalism, there was no other way to see it. This really bothered me. How is that possible? A 1:1 correlation?

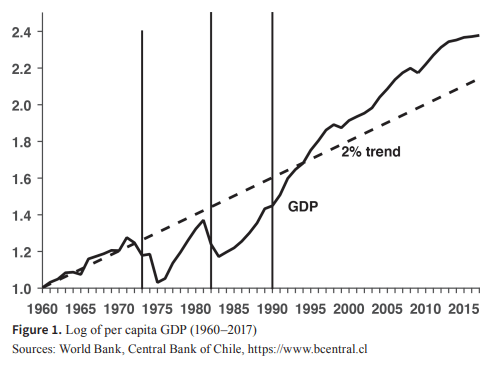

The deeper explanation which I am significantly more satisfied with is that price theory and what today I would consider standard supply and demand economic analysis was also not readily available. Although Hayek existed, the Chicago school was still young, the Solow Model and Schumpeterian growth were undertheorized and not yet ubiquitous insights (of course, even today one of our Nobel Prize winners is far more confident in strong industrial policy, “rethinking capitalism”, that Urho Kekkonen’s education reforms have a lesson for the US, and that big firms should have to share their data than I would be). Good arguments for bog standard capitalism were just thin on the ground through most of the 20th century, and the fact that it works was less a testament to its intellectual foundations than to the practical outworkings of common law and democracy plus property rights.

Towards the end of the trip, a small group of us went, of course, to Eric’s coffin shop! It was a short walk on foot down the beach. Eric makes the amazing fantasy coffins. You can be buried in a fast fish, dear reader as Herman Melville would wish it, or a loose fish, should you desire. Or a chicken in memoriam of your mother’s broth. Whether airliner or Nike shoe, Eric has the coffin for you. They are simple pine boxes and competitively priced. The shop was merely a shed with chain link. No proper display, too few commemorative items for sale. The parking was not good and the signage was nondescript. Eric is a simple, humble guy. He’s done expos in Paris, been featured in the Guardian, yet even some small adjustments could increase his profits. It would make sense to expand the business if he were interested.

I think Ghana is like this generally. Some small expenditures of 10k to 100k, and the long-run rate of return would be quite good, not to mention the value of increased economic activity and moving up the value chain. Of course, the forces of corruption are hard to contend with. But where there’s a will… there’s at least a cleaner beach.

Ghana was my first contact with hunger. Although, it was a very pleasant place, it was also evident that some people were smaller than they otherwise would be because of malnutrition. And only after I left did I realize that the doodad sellers, the women balancing bowls of bottles and snacks on their heads, including that guy late at night selling some purple ichor out of a plastic bottle, were in fact beggars in an equilibrium. Hence when one of our taxi drivers bought a bottle of water, it was semi-charitable purchase of convenience.

And that particular taxi driver had the best coup car. Racing red with a green racing stripe, a faux animal pelt carpet on his dashboard, a necklace and several charging cables drooping vinelike from his rearview mirror, a giant crack across the windshield, and racing car seat covers in green and red. He had the stuff of funk.

The Conference itself was wonderful. The organizers did a good job mixing freedom and control as the non-Africans can be trusted no more than Marcus Brody to not get lost. If you wanted to explore on your own you could, but at no point did you need to.

We visited Christiansborg Castle (isn’t that redundant?) and there the office of two-time coup leader, Jerry Rawlings. Sadly the castle is in disrepair, and the tourism board seems to not care about or take any professional pride in it. Another missed opportunity.

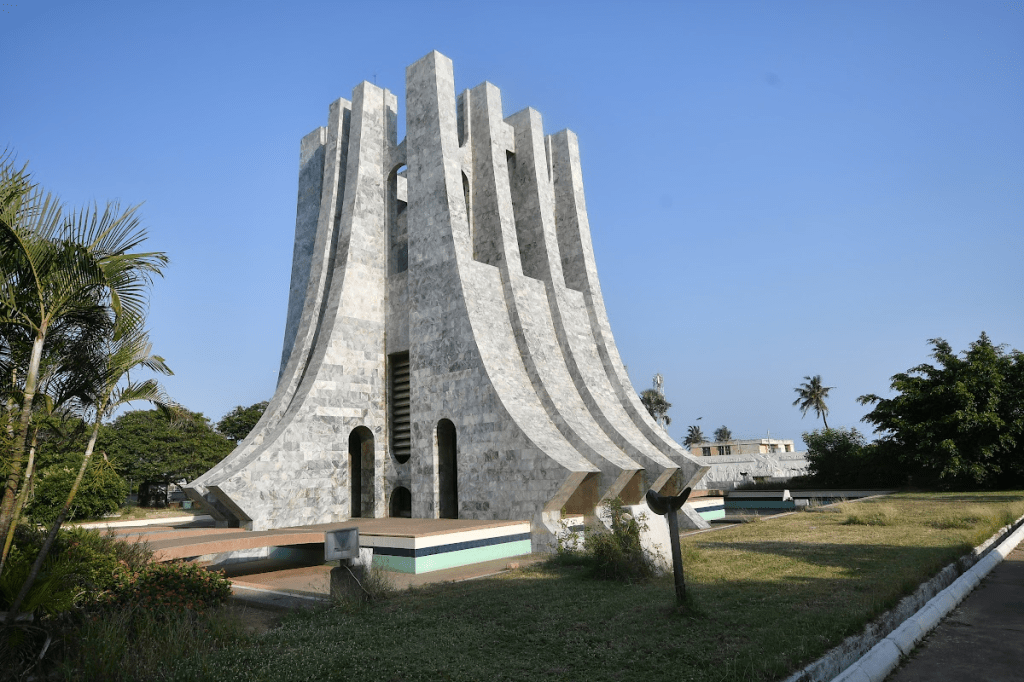

The tomb of Nkrumah, which is truly a stunningly beautiful monument to the independence leader would fill me with patriotism, if I were a Nkrumah fan. We had a conversation about if you could give Nkrumah advice what would it be? One answer: wait 20 years. Independence isn’t as good as you think it will be.

The conference sessions were quite good. Finally got to meet my friend Luke Olayemi in person. He ran one session on developing new concepts for describing internet social life, which I thought was very fun. And I want to see more ideas from him.

We had a session on U.S. – Africa relations. In the wake of major US aid cuts, emotions were complicated by the feeling of great frustration with African governments. If it were solely a matter of the U.S. refusing aid, that would be one thing, but the incompetence of the government means they lack the capacity to react usefully to a shortfall in medical aid. And so there was spirited disagreement about how to think about the US – Africa relationship, and what to hope for.

I met a nuclear medicine doctor from Botswana who is opening up a clinic. He can confirm there are more cows than people in Botswana; he owns 3. I noticed the pan-African comraderie was quite strong. People talked about other African countries the way we talk about other US states. This made me quite optimistic for future economic and political unions arising. I asked some of the ladies which country has the best men for romance and marriage. The answer: for romance Nigeria, but for marriage Uganda. A Nigerian later responded that female view is because Nigerian women have trained Nigerian men in the art of excessive and conspicuous expenditure on their girlfriends.

Jan Grzymski, leader of 89School, a program on Poland’s post-soviet liberalization showed off his political science board game How to Win Brexit. We did a mini-session, where Rebecca Lowe and Rasheed Griffith blasted me (Donald Tusk) into the smallest of smithereens with their much more serious and deep knowledge of the EU.

I recruited Sam Enright at noon to help me measure the sunlight so that I could calculate the relative latitude of St. Louis and Accra myself. I was off by a couple of degrees, but the measurements were done two weeks apart. It wasn’t bad for some slapdash measurements.

I enjoyed talking to Samukai about Liberian census tracts, David Perell about art, Rebecca Lowe about philosophy and novels, and several of the younger crowd who are working on academic competition prep in Kenya, Nigeria, and a few other places. Joshua Walcott and I went several rounds on religion and morality. Duncan Mcclements and I went many rounds on economic development and FDI. Lorenzo talked about building the tourism industry in Belize, Lamin on building an ambulance network in Gambia.

Andy Matuschak and I enjoyed a lively dinner conversation about Great Books and 20th century learning and possibility of diminishing returns.

Rasheed nudged me to work on Spanish more and get involved in politics. Advice I have taken.

Every EV conference has a takeaway line. This conference I felt the message was “good governance is hard to find.”

Retrospectively, I wish I had offered a session on what Classics has to offer Africa, building off the experience of Malawi, and discussing the origins of good governance in the classical world and soliciting for African examples.

I would like to tarry and indulge in divulging every insight and experience in Ghana, because to write about one’s travels is to travel twice.

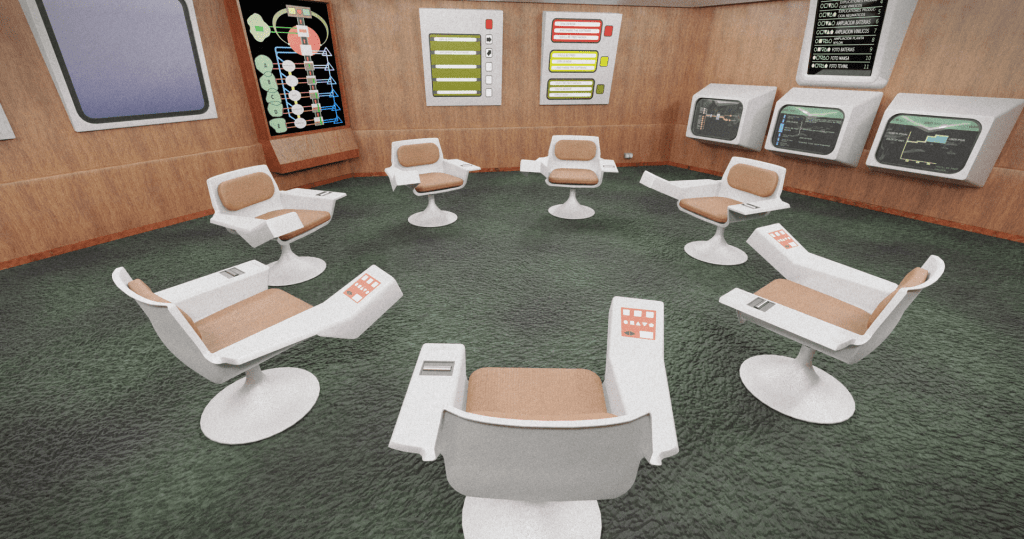

In October, Sam Enright pulled off a great coup at the University of Chicago with his conference on Milton Friedman. We met at the Quadrangle Club around a large polished wood table, in a secluded academic board room, served fresh water by the pitcher. The type of place where one could plan all sorts of thing… but not secure enough to plan too much global disruption: it’s not enough in plain sight!

Since it was my first visit to the beautiful University of Chicago, I was able to take time to wander early in the morning. I drove into the city from the west and as the sun rose over downtown I listened to Tyler Cowen’s tour of choral music with Rick Rubin. That was such treat, Monteverdi and Shaw as the sun rose up behind the shoulders of the iconic Willis Tower.

When I got to campus parking was easy and the journey was light.

We started with a group in coffee shop and immediately got into full geek mode.

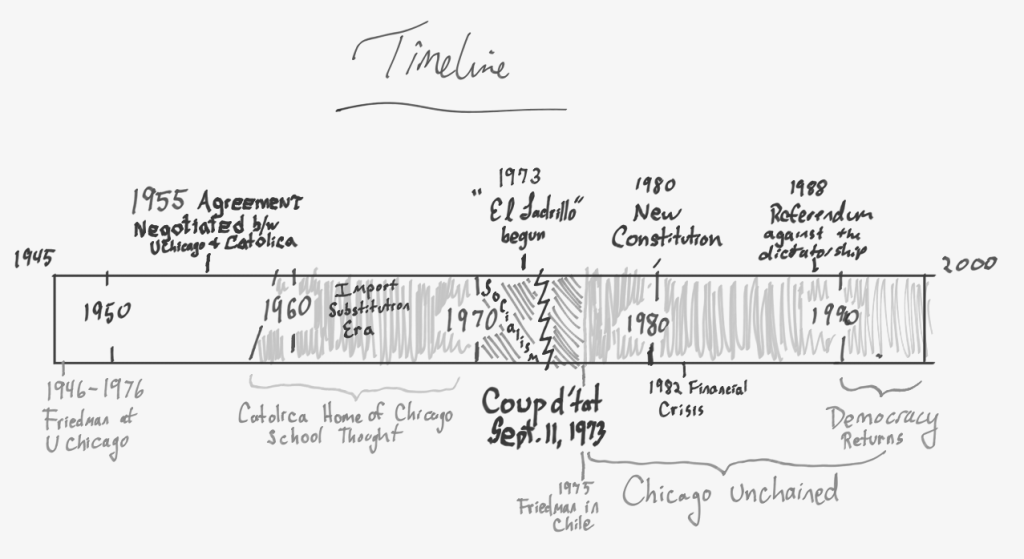

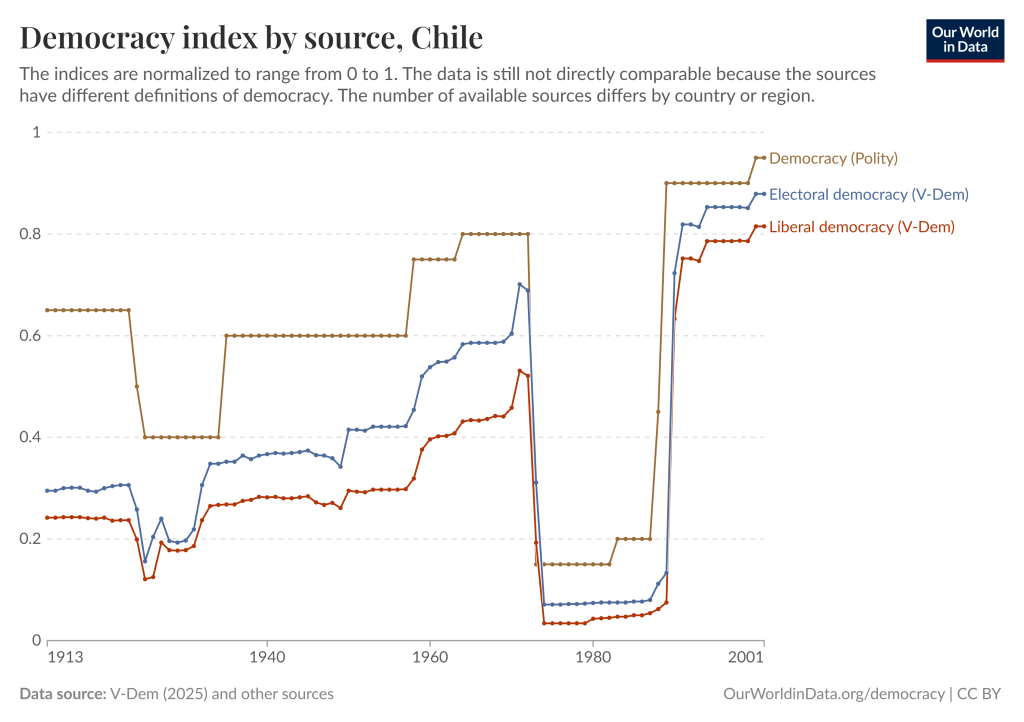

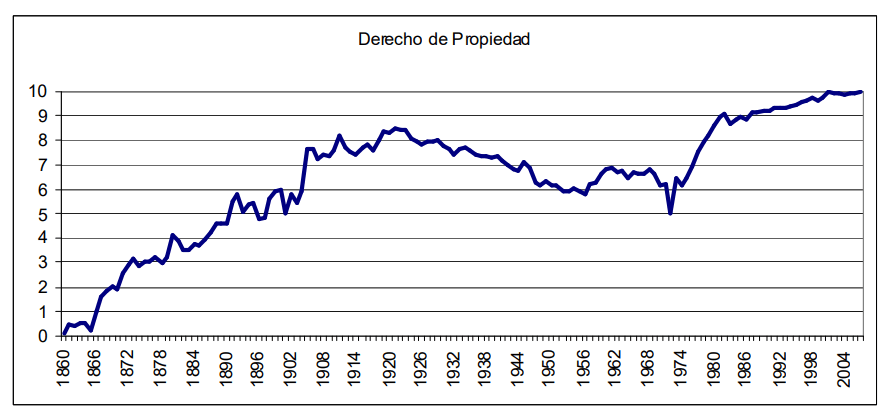

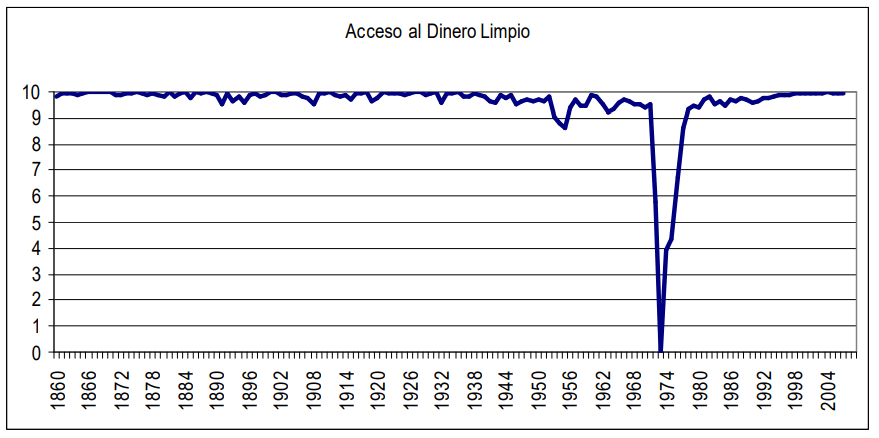

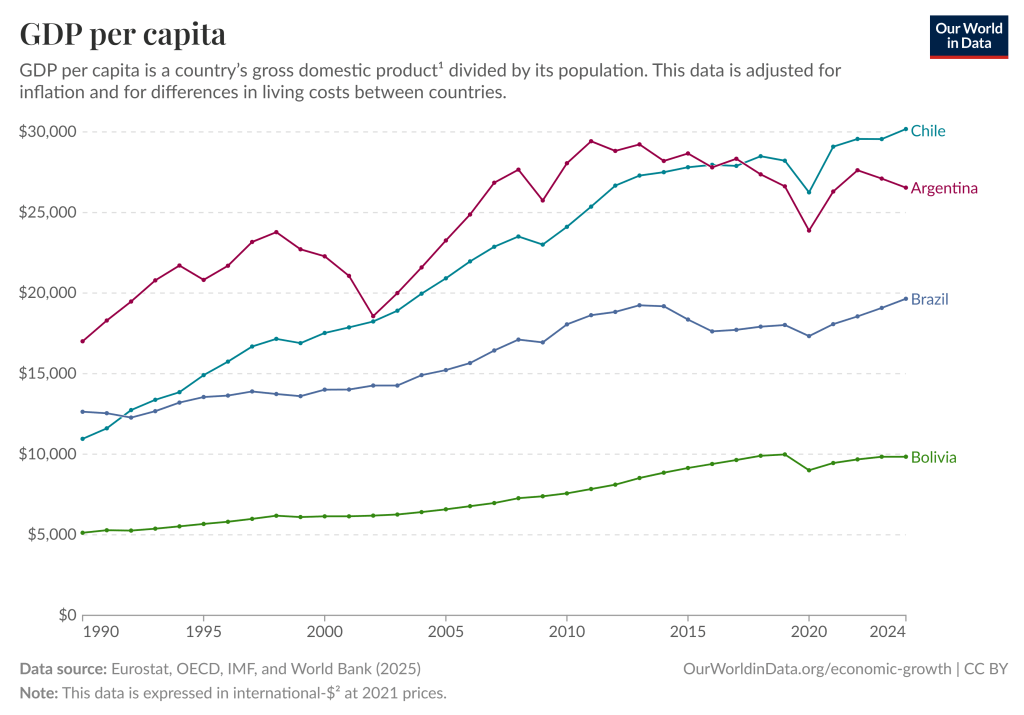

Kadambari Shah started off the conference with a session on Milton Friedman in India, which was great for its parallels to Milton in Chile.

Agnes Callard and Rebecca Lowe brought philosophical heat and burned away some of Milton’s superficial philosophizing. Rebecca impaled Milton’s distinction between political and economic systems when discussing capitalism and socialism, while Agnes scattered three handfuls of dust on Milton’s logical consistency in “The Moral Obligation of Business is to Maximize Profit”. Both certainly depressed any claim Milton could make to being a logically consistent philosopher.

Robin Hanson presented on Milton Friedman on mechanism design, and mostly focused on explaining the deeply limited case for government intervention in alleged market failures. This discussion was also helped along by some quick insight from the extremely sharp Anup Malani.

(Anup by the way once again excoriated my argument that hybrid education provides economic savings. This got us into the timely argument about Baumol and whether education services can actually experience new efficiencies. Then, when I made an argumentative gaffe concerning total cost, he pounced like a tiger, lithe and deadly, and ended my argument. It was a glorious massacre. I gathered up my entrails a day later and reformulated into something he could accept.)

Sam E. was saddled with Milton Friedman on Monetary Theory. Despite the monumental task, a task he shook from his remit in vain, Sam did a great job, and started with a statement that very much compelled my interest. He said that he loves the way Milton’s Monetary History of the United States is written. That it is a good causal history, and he wondered why there are not more like it.

I have a whole list of books that fit my preferred style of historical writing which I will be sending him shortly.

We had good lunch conversation over the standard questions of global monoculture and cultural churn. I am more optimistic than many others, but probably because I spend most of my time in a small community that is intellectually stimulating and has a high birth rate. I don’t feel the stultifying effects of the academic landscape that my peers who teach do.

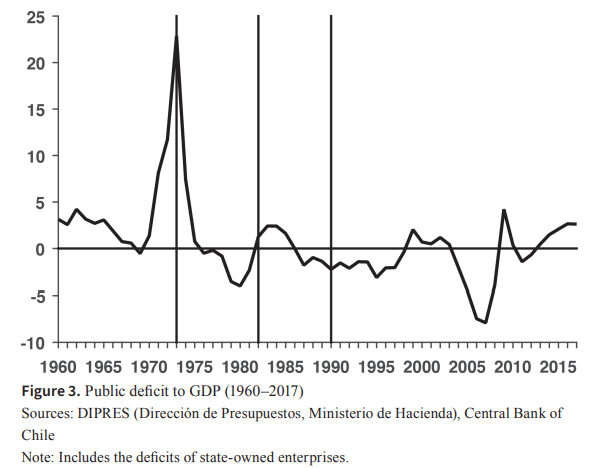

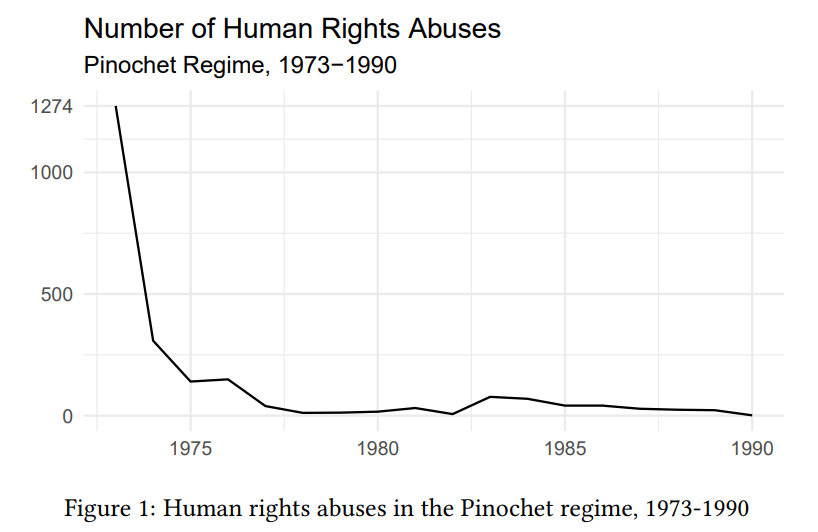

My own presentation on the economic history of Chile went very well despite the late hour and the growing exhaustion of the participants.

The best podcasts this year were:

Statecraft by Santi Ruiz. Santi Ruiz interviews excellent researchers and practitioners of everyday governance. Great background if you want get involved in civics at any level.

Marginal Revolution Podcast – Tyler and Alex getting back to just talking economics. I really like it.

Dwarkesh Podcast – Sarah Paine lectures on Russia and China from the Naval War College.

Best films I watched this year were:

A Touch of Sin (2013) Chinese film about sin that is a series of vignettes. Some of which pretty were tough to watch. Seriously good film though.

Paths of Glory (1957) Stanley Kubrick film on a WWI court martial. Riveting meditation on the hell of war and the injustice of scapegoating.

Live Die Repeat (2014) Tom Cruise. A riveting and interesting action film.

Through the Olive Trees (1994) Kiarostami. Finally finished the Koker Trilogy. It was a really lovely film, and I am such a sucker for this type of Umerto-Eco elegant conceit of nested realities. Kiarostami is like a Renaissance courante between realism and a protagonist’s incredible persistence for love.

But the best cinema experience was renting out a theater and having a bunch of my friends and the St. John Paul II crowd watch the French film Of God’s and Men (2010). That indeed was a great experience. We had about 50 attendees. Thank you Robby for collaborating on this and taking care of technical aspects.

I taught Chad Kim’s new book Primer on Ecclesiastical Latin to my Latin students this year. It is the best in the genre of ecclesiastical Latin textbooks. The layout of the book is straightforward and made to pair well with students who have taken or are going through Lingua Latina (this does not apply to my students), but I appreciate the grammatical lineup.

Good introductory Latin textbooks provide limited and essential vocabulary that prepares students for reading particular authentic texts. When it comes to preparing students for ecclesiastical and medieval readings, especially scripture and St. Augustine, this book is head and shoulders the best in the business. It is also complete enough to be useful for self-study.

—

In books, I thought it was a thin year for me. I read a lot, but not a ton that really rocked.

Middlemarch by George Eliot – if you know, you know. I started it before the Middlemarch craze seized the world and finished after the wave had passed: worthy though it is of eternal hype.

I read a lot of Leibniz in 2025. Maria Rosa Antognozza’s biography is the secondary source to read. Maria sadly passed away before I got to talk to her. There are a million did-you-knows one could offer about Leibniz, but a recent one was that he wrote three papers on mortality tables and life insurance. And naturally the reason the royal we are interested in Leibniz is because of the style of intellectual life he lived – both at the cutting of philosophy, mathematics, and natural philosophy and steeped in the Aristotelian and Lutheran traditions – both concerned with finding new angles on traditional intellectual problems and determined to break out into new fields – a role model for what verve looks like.

And in academic writing, I found great interest in Edna Ullman-Margalit and Richard Posner (the Pos!) and various other law and economics writing.

—

Music was a tragic year. My favorite radio station 88.1 KDHX after two years of internal dissensions and infighting gave up the ghost. The station was my number one way of being exposed to new music in folk, alt-rock, “world music”, and really any genre except classical. The loss has caused me to be more intentional. I have been prowling archive.org for old KDHX playlists. I have turned up two awesome albums from 2020.

Music of the Sani by Manhu. Rural Yi music from southern China. Super delightful. Only a handful of views on YouTube.

Kompromat by I LIKE TRAINS. Alt-rock eery vibes with lyrics written entirely in cliche and idiomatic expressions.

I have been making playlists to atone to the muses for my dereliction of responsibility in discovering new music and cultivating wanderlust.

December Playlist.

January Playlist.

Karlsson Goals:

Henrik Karlsson gave me the idea to send myself check-in emails on a three month delay to gauge my progress and breakdown long term goals into intermediate steps. It has been a useful exercise, because three months is a long enough time span to show a good sized delta between revealed and considered preferences.

Some goals for 2026:

- Find some people who want to take me to China (or really anywhere in Asia). I am always willing to trade lectures, research, and struggle sessions for travel .

- Run a mini-conference on the poetry and literary criticism of T.S. Eliot.

- Build and run another logic tournament

- Improve St. Louis County zoning regulation

- Foster my local collective of artists and architects